The quiet growth of Brazil’s Venezuelan population

The Venezuelan population in Brazil has nearly doubled in just two years, while the ongoing development of the National Migration Policy proves an opportunity to improve coordination and integration.

Consulte aqui uma versão em português do boletim traduzida por inteligência artificial.

Se puede acceder aquí a una versión en español traducida por inteligencia artificial.

As many countries across the Americas (and globe) struggle to receive and integrate newcomers, Brazil’s experience responding to Venezuelan migration offers an interesting case, albeit not without its own flaws. Over 90% of Venezuelans in Brazil have regular status, and the country legally confers equal access to the universal health care system and education—regardless of immigration status—as well as relatively easy access to work permits and social assistance programs. The lusophone country has grown to become the third-largest receiver of Venezuelans in Latin America and the Caribbean, and yet most of the population has not registered that demographic shift. The estimated 477,500 Venezuelans in the country are a drop in the bucket among a total population of more than 210 million.

Roraima, Brazil’s isolated Amazonian state bordering Venezuela, has received the vast majority of Venezuelans entering the country. Many Venezuelans there have acute protection needs; jobs are scarce, and homelessness and hunger are rampant. Tensions have persisted with receiving communities, and migration has managed to permeate local politics in recent years.

But elsewhere, the rest of Brazil generally is not thinking about immigration. And when they do, some of the nationalities that come to mind first are Angolans, Afghans, and Haitians—and more historically Syrians, Lebanese, Bolivians, Japanese, Italians, and Germans, among others. As of last month, NGOs that I visited that provide services to migrants in São Paulo were spending more of their time assisting Afghans and Angolans than Venezuelans. This relative invisibility has meant that outside of Roraima, Venezuelans in Brazil have not received the same level of xenophobic or criminalizing backlash they have experienced at times elsewhere in the hemisphere.

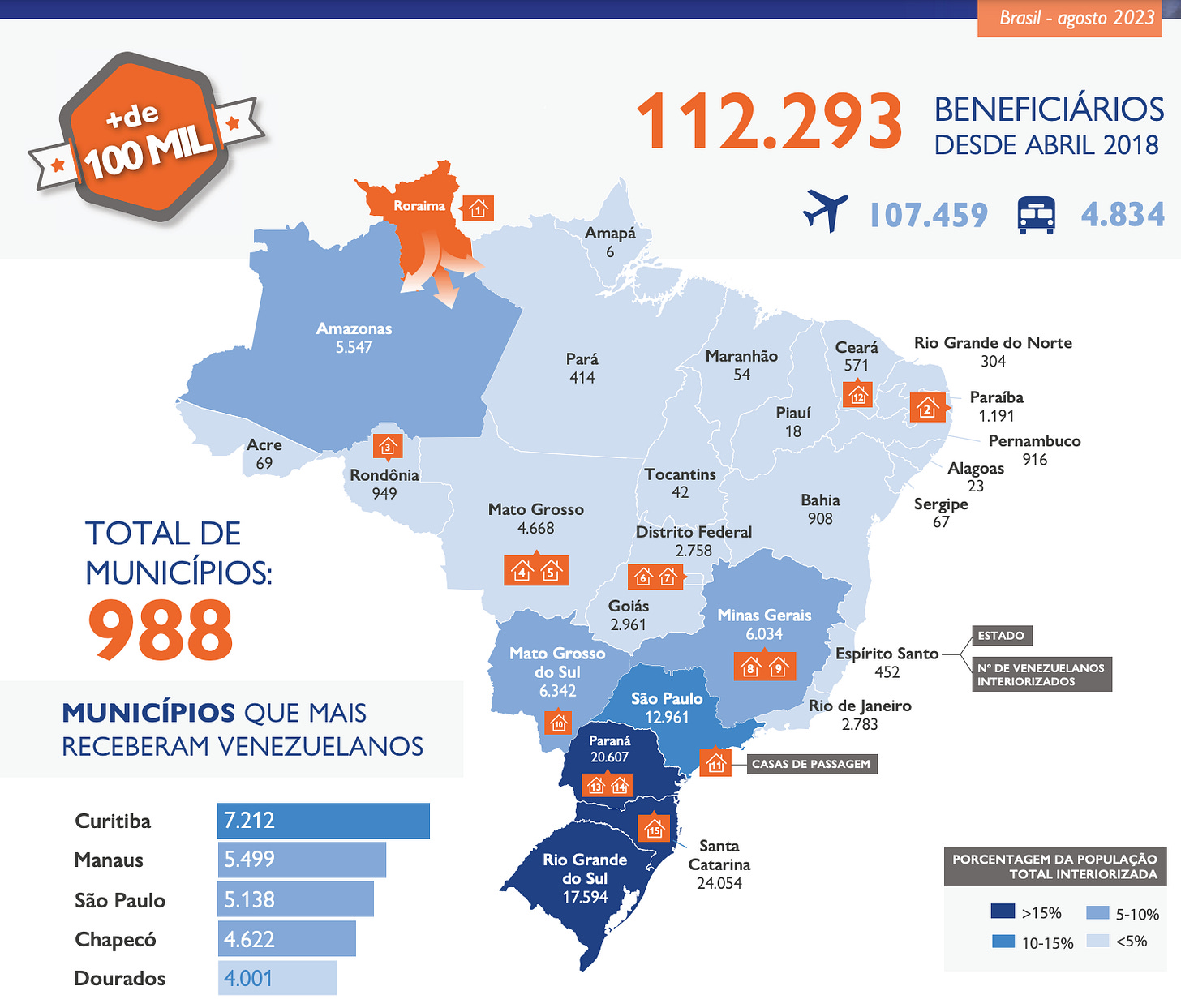

The Brazilian government has used Operation Welcome, begun in 2018, to respond to Venezuelan migration and the dire situation in Roraima. Interiorization, a voluntary relocation program to move Venezuelans out of the state, has been key to the approach and to distributing responsibility away from the high profile situation in the north and towards areas with greater opportunities and public services. 112,293 Venezuelans have taken part in the interiorization program thus far, traveling to 988 of Brazil’s 5,568 total municipalities, a major achievement. One 2021 survey of interiorized Venezuelans found that they were working at similar rates to those of their Brazilian peers, albeit more likely to be doing so informally.

Box 1. Where are Brazil’s Venezuelans located?

It is impossible to say with certainty how the Venezuelan population in Brazil is distributed across the country, and a general consensus of uncertainty was shared with the Americas Migration Brief from government, civil society, academic, and multilateral actors alike. One unofficial estimate shared with the Americas Migration Brief by a well-placed source found around 100,000 or so Venezuelans currently remaining in Roraima—which would imply that somewhere in the ballpark of 80% of the 477,500 Venezuelans in Brazil reside elsewhere in the country. Among these, 112,293 have taken part in interiorization, meaning that it is likely that a greater number of Venezuelans have left Roraima for elsewhere in Brazil independently of the interiorization program. There is no definitive way to follow where these migrants have gone or their exact numbers. And others still have flown to Brazil and entered the country in states other than Roraima.

You can find more details about the distribution and characteristics of those migrants that have taken part in the interiorization program here and in the image below. Note that this data does not follow where they may have gone after taking part in the program and is not necessarily reflective of their current geographic distribution.

(Image source: R4V)

The challenge with interiorization—whether through the official program or independently—is that the rest of the country simply does not have the experience with migration to effectively respond to this population. Few municipalities have the institutional knowledge or legal frameworks or operations set up to properly support integration. Venezuelans need language classes, housing support, job training, and assistance in connecting to employers. And at the most fundamental level, they need shelter; but the country lacks significant shelter space even in São Paulo, which has the most robust reception infrastructure and greatest history of receiving migrants. According to government data from 2022, Venezuelans represent a disproportionately large number of Brazil’s homeless population.

One key opportunity to improve current conditions is strengthening coordination. In many cases, local governments do not even necessarily know when or where Venezuelans have arrived, and there is a critical lack of coordination between Operation Welcome and local officials. I have heard multiple times in Brazil the phrase “Mandam e tchau” (“They send and say goodbye”) in reference to the interiorization program. This lack of continued attention is particularly of concern in that there is insufficient oversight surrounding employment-based interiorization pathways to ensure migrants are not being exploited. Similarly, there is a lack of oversight and verification that social reunification interiorization pathways—which represent about half of all cases—are genuine and that migrants do not arrive to a precarious or abusive environment. Shelter-to-shelter (“Institutional”) pathways have been the most durable but struggle for capacity.

Even if challenges exist to integrate Venezuelans and monitor cases post-interiorization, the outlook moving forward is positive. The Lula administration, inaugurated at the start of this year, has placed greater emphasis on migration policy and has sought to adopt an inclusive and rights-based approach. Following the passing of the country’s landmark Migration Law in 2017, successive presidents failed to kickstart the development of the National Migration Policy called for in the 2017 law—the new administration has held working groups with stakeholders and is currently in the process of writing and validating a draft policy.

The National Migration Policy will outline regulations, technical operations, and crucially help promote greater coordination across and within different levels of government. The policy still faces the difficulty of surpassing bureaucratic inertia and interministerial tensions, but significant progress has been made; the Lula administration has restarted dialogues with civil society and boasts greater political will than its predecessors for change. Also of note, the government has a National Policy on Indigenous Mobility in the cards, which would be the first of its kind in the region. Indigenous Venezuelans in Brazil have faced unique challenges, as IOM has helped document.

The nearly half a million Venezuelans in Brazil are often overlooked outside of Roraima, but are a fast-growing population in need of a stronger reception and integration architecture in their new communities. Greater governmental coordination and oversight are critical to ensuring that migrants can capitalize on the promise of better opportunities offered by interiorization. With this, the development of the National Migration Policy proves a key chance for progress.

This article is the product of a recent trip to Brazil, where I spoke with over 20 individuals from federal and local levels of government, civil society, multilaterals, and academia.