Both challenges and opportunities ahead for planned expansion of Caribbean free movement

Despite obstacles, Caricom’s planned expansion of free movement is an opportunity for a new era in Caribbean integration and mobility.

Se puede acceder aquí a una versión en español traducida por inteligencia artificial.

Une version française traduite par intelligence artificielle est accessible ici.

Een Nederlandse versie vertaald door kunstmatige intelligentie is hier beschikbaar.

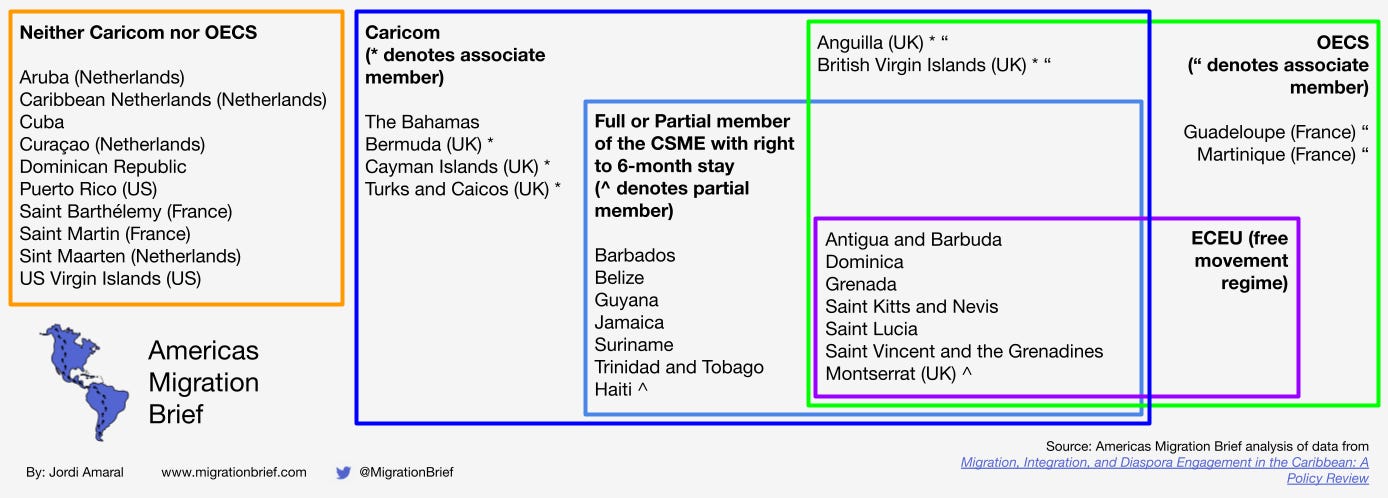

Earlier this month, the Caribbean Community (Caricom) announced that it would look to establish “free movement for all Caricom nationals by March next year.” Although a limited free movement regime already existed in the form of access to a visa-free six-month stay and access to work and stay under the Skills Certificates initiative for certain professions, this announcement marks the potential for a new era in Caribbean integration and mobility.

When conducting research on Caribbean migration in the past, stakeholders across the region were generally skeptical of such a move to expand integration in the bloc. And yet, here we are. The 50th anniversary of the establishment of Caricom proved to be the moment for reigniting the mission of regional integration and development. At bare minimum, the announcement is a tremendous symbolic achievement.

For more on Caribbean migration and further details about existing free movement regimes like the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) Eastern Caribbean Economic Union (ECEU), check out the recent report I co-authored with colleagues from the Migration Policy Institute and Inter-American Development Bank: Migration, Integration, and Diaspora Engagement in the Caribbean: A Policy Review.

There remains a skepticism among many about the implementation of these bold aspirations. As I wrote with my co-authors in a recent MPI-IDB report on Caribbean migration, the current, more limited iteration of free movement that exists within Caricom, known as the Caricom Single Market & Economy (CSME), has not reached full implementation. Although visa-free six-month stays may be facilitated administratively, they are not always formally incorporated in the legal code; just three of the 12 full CSME members allow entry for Skills Certificate holders of all 12 eligible professional categories.

Furthermore, some of the same caveats that allow governments to reject would-be beneficiaries of CSME six-month stays—specifically national security and public charge reasons—could potentially remain in the planned expanded version of free movement. External pressures to halt northbound transit migration may also impede true access, as seen with Belize’s implementation of visa restrictions for Haitians and consideration of restrictions for Jamaicans. Most notably, though, it has already been announced that Haiti will not be included in the new free movement regime (and Haitians currently only have visa-free access to Grenada, despite the CSME and the Caribbean Court of Justice’s ruling in Shanique Myrie versus Barbados).

Haitians have very real protection needs amid an acute humanitarian crisis with no foreseeable resolution as of yet. At the same time, the move to exclude Haitians responds to real concerns from local governments and communities about capacity to receive and integrate them—and these same capacity challenges exist for the reception of other nationalities, too. The tough reality is that the inclusion of Haitians would have likely made expansion of the free movement regime a nonstarter.

The move is pragmatic and improves the viability of the free movement regime amid an environment in which people are concerned about access to social programs and jobs and xenophobia is on the rise. Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley has also noted that ahead of the planned March 2024 rollout of the policy, the Caricom member states will still need to agree upon what minimum rights will be guaranteed for migrants in receiving countries. After all, capacity is already an issue in many Caribbean countries for their own nationals—a problem seen across much of the Americas more generally.

And yet, despite it all, the announcement of expanded free movement is a real chance for greater prosperity in the Caribbean region. Promoting free mobility is a useful tool for growing economic integration and building opportunities for the region’s peoples, who have historically primarily migrated for economic purposes. As Guyana continues to develop a burgeoning energy sector and hopes to diversify its economy, jobs will need to be filled. Other industries across the region would also benefit from increased labor mobility, including tourism, agriculture, and services. And increased movement of people will additionally prime the environment for increased movement of goods and services through trade.

In addition, expanded free movement will be key for facilitating protection to those in need. This is particularly true for those impacted by ever-growing environmental disasters, as well as those displaced by slower-onset impacts of climate change such as rising sea levels and drought. The OECS’s ECEU free movement regime and the CSME’s six-month stay have both already proven useful tools for such action in the past, as seen with responses to Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Amid the intensification of climate change and burgeoning possibilities for economic development, the expansion of free movement offers an opportunity for greater integration within Caricom and the Caribbean more widely. Obstacles to implementation remain, but this month’s announcement maintains the potential to become a watershed moment for the region.